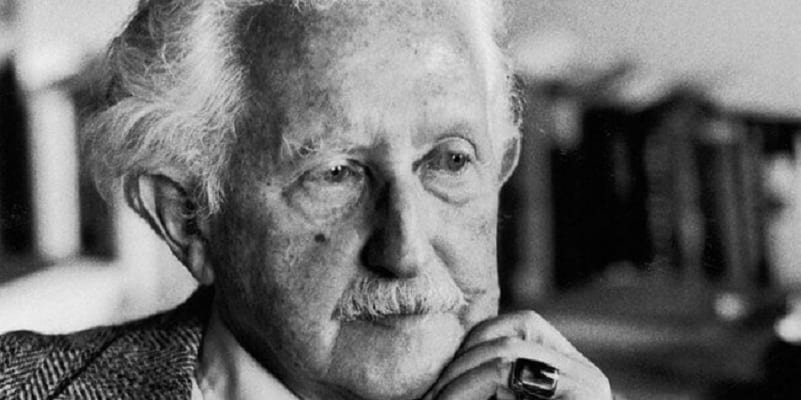

Erik Erikson biografie en quotes

Erik Erikson (geboren 15 juni 1902 – overleden 12 mei 1994), voluit Erik Homburger Erikson, was een Amerikaanse psychoanalyticus die bekend is geworden met zijn werken over sociale psychologie, individuele identiteit en de interacties van psychologie met geschiedenis, cultuur en politiek. Erik Erikson ontwikkelde en beschreef voor het eerst het concept van een identiteitscrisis.

Erik Erikson biografie

Erik Erikson werd geboren in Frankfurt, Duitsland. Hij was de zoon van Karla Abrahamsen en Waldemar Isidor Salomonsen, een joodse effectenmakelaar. Hij werd geboren op het moment dat zijn moeder net uit elkaar was met zijn biologische vader, van wie geen informatie beschikbaar is.

Kort na zijn geboorte verhuisde zijn moeder met Erik naar Karlsruhe. In Karlsruhe werd ze verpleegster en trouwde ze met kinderarts Theodor Homburger.

In 1911 werd Erik officieel geadopteerd door zijn stiefvader Theodor Homburger en nam hij zijn achternaam aan. Hij groeide op zonder te weten wie zijn biologische vader was, iets dat voor hem werd verzwegen. Hij worstelde zijn hele jeugd met zijn identiteit omdat hij voelde dat zijn stiefvader hem niet volledig accepteerde, zoals hij dat wel deed met zijn eigen dochters.

De ontwikkeling van zijn identiteit en de daarbij behorende psychische problemen lijkt dus een van de grootste onderwerpen geweest te zijn in het vroege leven van Erik Erikson. Dit stond later ook centraal in zijn theoretische werk. Als volwassene schreef hij over zijn identiteitsverwarring, zoals hij dat noemde.

Hij beschreef zijn staat van zijn als tussen neurose en adolescente psychose. De dochter die hij later zou krijgen beschreef dat de echte psychoanalytische identiteit van haar vader pas geopenbaard werd toen hij zijn achternaam verving door een naam die hij zelf had bedacht: Erikson.

Erik Erikson was een lange en blonde jonge met blauwe ogen die was opgegroeid in een Joodse omgeving. Hierdoor was hij vaak een doelwit van pesterijen en onverdraagzaamheden, door zowel Joodse als niet-Joodse kinderen. Op de zogenaamde tempelschool werd hij gepest omdat hij Noors was, terwijl hij op de middelbare school gepest werd omdat hij Joods was.

Erik miste een algemeen interesse in school en studeerde daarom niet af aan een universiteit. Hij ontwikkelde wel een interesse voor kunst, geschiedenis en talen. Na zijn middelbare school ging Erik daarom naar de kunstacademie in München, en niet naar de medische universiteit, zoals zijn stiefvader graag gewild had.

Ook op de kunstacademie vond Erik niet helemaal zijn plek en stopte al snel. Hij begon een lange zwerftocht door Duitsland en Italië, samen met zijn jeugdvriend Peter Blos. Tijdens zijn reizen verkocht hij schilderijen of schetsen aan mensen die hij ontmoette.

Uiteindelijk realiseerde Erik Erikson zich dat hij nooit een echte kunstenaar zou worden en verhuisde hij weer naar Karlsruhe. Hier werd hij tekenleraar. Gedurende deze tijd werd Erik ingehuurd door families om tekenles te geven aan hun kinderen. Hij werkte fijn samen met kinderen en ontmoette op die manier ook families die dichtbij Sigmund Freud en zijn dochter Anna stonden.

Gedurende deze periode bleef hij worstelen met vragen over zijn identiteit, zijn biologische vader en over concurrerende ideeën over etnische, religieuze en gemeenschappelijke identiteiten. Hij raakte bevriend met Anna Freud, die ook een psychoanalyticus was. Hij werd in 1927 uitgenodigd door Anna om kunst, geschiedenis en aardrijkskunde te doceren aan een privéschool in Wenen, Oostenrijk. Hij raakte geïnteresseerd in de psychoanalyse en deed een opleiding om zelf psychoanalyticus te worden.

Hij focuste vooral op de ontwikkeling van kinderen en schreef zijn eerste onderzoek in 1930, net voordat hij zijn opleiding voltooide. In 1933 werd hij gekozen als lid van het Weense Psychoanalytisch Instituut. In datzelfde jaar emigreerde hij naar de Verenigde Staten toen de nazi’s Duitsland overnamen.

Hij werkte een tijdje in Boston en in verschillende functies bij instituten als het Massachusetts General Hospital, Judge Baker Guidance Center en Harvard Medical School and Psychological Clinic.

In 1936 trad Erik Erikson toe tot de Harvard Universiteit en werkte hij aan het Institute of Human Relations. Hij bestudeerde in die periode ook een aantal kinderen in een Sioux-reservaat in South-Dakota. Hij verliet Harvard University in 1937 en begon als lid van de staf van de California University. Daar was hij verbonden aan het Institute of Child Welfare en hij opende tevens zijn eigen praktijk.

Erikson verliet de Universiteit van California en begon les te geven aan het Austen Riggs Centre. Dit was een belangrijke psychiatrische behandelingsinstelling in Stockbridge. Hij besteedde veel tijd aan het bestuderen van kinderen uit verschillende omgevingen en kinderen van verschillende rassen. Zijn observaties leidden tot het beroemde boek Childhood and Society. Het boek werd een introductie tot de wereld van de identiteitscrisis.

Erikson bedacht 8 ontwikkelingsstadia van mensen, die elk het individu confronteerden met andere psychosociale eisen. Deze gingen door tot op late leeftijd. Persoonlijkheidsontwikkeling vindt volgens Erikson plaats door een reeks crises die door het individu moeten worden overwonnen en geïnternaliseerd ter voorbereiding op de volgende ontwikkelingsfase.

In het boek Young Man Luther uit 1958 combineerde Erikson zijn interesse in psychoanalytische theorie en geschiedenis in een onderzoek naar Maarten Luther om vast te stellen hoe hij in staat was om te breken met een bestaande religieuze establishment om een nieuwe manier te creëren om naar de wereld te kijken.

In 1960 ging Erik Erikson terug naar de Harvard University en werd hij hoogleraar menselijke ontwikkeling. Hij werkte hier tot aan zijn pensioen en schreef samen met zijn vrouw verschillende artikelen en boeken over onderwerpen gerelateerd aan psychologie. Na de start van zijn pensioen in 1970 bleef Erik Erikson emeritus hoogleraar tot aan zijn dood.

Bekende quotes

- “Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive. If life is to be sustained hope must remain, even where confidence is wounded, trust impaired.”

- “Healthy children will not fear life if their elders have integrity enough not to fear death.”

- “Anxieties are diffuse states of tension (caused by a loss of mutual regulation and a consequent upset in libidinal and aggressive controls) which magnify and even cause the illusion of an outer danger, without pointing to appropriate avenues of defense or mastery.”

- “Life doesn’t make any sense without interdependence. We need each other, and the sooner we learn that, the better for us all.”

- “Doubt is the brother of shame.”

- “We are what we love.”

- “We cannot leave history entirely to nonclinical observers and to professional historians.”

- “Babies control and bring up their families as much as they are controlled by them; in fact the family brings up baby by being brought up by him.”

- “The more you know yourself, the more patience you have for what you see in others.”

- “In the social jungle of human existence, there is no feeling of being alive without a sense of identity.”

- “You see a child play, and it is so close to seeing an artist paint, for in play a child says things without uttering a word. You can see how he solves his problems. You can also see what’s wrong. Young children, especially, have enormous creativity, and whatever’s in them rises to the surface in free play.”

- “Adolescents need freedom to choose, but not so much freedom that they cannot, in fact, make a choice.”

- “There is in every child at every stage a new miracle of vigorous unfolding.”

- “A creative man has no choice. He may come across his supreme task almost accidentally. But once the issue is joined, his task proves to be at the same time intimately related to his most personal conflicts, to his superior selective perception, and to the stubbornness of his one-way will; he must court sickness, failure, or insanity in order to test the alternative whether the established world will crush him, or whether he will disestablish a sector of this world’s outworn fundaments and make place for a new one.”

- “No man can claim that he is absolutely in the right or that a particular thing is wrong because he thinks so, but it is wrong for him so long as that is his deliberate judgment. It is therefore meet that he should not do that which he knows to be wrong, and suffer the consequence whatever it may be.”

- “And yet the sternness sometimes displayed in your letters to your children bespeaks an appalling sense of doom, as if they, as the product of your sin, had no chance for salvation except as partners in your renunciation.”

- “If some busybody were to cross-examine me on the chapters already written, he could probably shed much more light on them, and if it were a hostile critic’s cross-examination, he might even flatter himself for having shown up [make the world laugh by revealing] the hollowness of many of my pretensions.”

- “Nevertheless, it is true that the first discipline encountered by a young man is the one he must somehow identify with unless he chooses to remain unidentified in his years of need. The discipline he happens to encounter, however, may turn out to be poor ideological fare; poor in view of what, as an individual, he has not yet derived from his childhood problems, and poor in view of the irreversible decisions which begin to crowd in on him.”

- “An infant of two or three months will smile at even half a painted dummy face, if that half of the face is fully represented and has at least two clearly defined points or circles for eyes; more the infant does not need, but he will not smile for less. The infant’s instinctive smile seems to have exactly that purpose which is its crowning effect, namely, that the adult feels recognized, and in return expresses recognition in the form of loving and providing.”

- “None was to touch any one’s property on the way. They were to bear it patiently if any official or non-official European met them and abused or even flogged them. They were to allow themselves to be arrested if the police offered to arrest them.”

Publicaties, boeken en artikelen van Erik Erikson

- 2017. The concept of identity in race relations. In Americans from Africa (pp. 323-348). Routledge.

- 1995. A way of looking at things: Selected papers, 1930-1980. W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1998. The life cycle completed (extended version). W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1994. Vital involvement in old age. W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1994. Identity and the life cycle. W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1994. Insight and responsibility. W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1993. Young man Luther: A study in psychoanalysis and history. W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1993. Gandhi’s truth: On the origins of militant nonviolence. W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1993. Childhood and society. WW Norton & Company.

- 1984. Reflections on the last stage—and the first. The psychoanalytic study of the child, 39(1), 155-165.Erikson, E. H. (1980). On the generational cycle an address. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 61, 213-223.

- 1980. Themes of work and love in adulthood. Harvard University Press.

- 1979. Dimensions of a new identity. WW Norton & Company.

- 1978. Adulthood. WW Norton & Company.

- 1977. Toys and reasons: Stages in the ritualization of experience. W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1976. Reflections on Dr. Borg’s life cycle. Daedalus, 1-28.

- 1970. Reflections on the dissent of contemporary youth. Daedalus, 154-176.

- 1970. Autobiographic notes on the identity crisis. Daedalus, 730-759.

- 1967. Eight ages of man. Klassiekers van de kinder-en jeugdpsychiatrie II, 258.

- 1966. D. ontogeny of ritualization: Ontogeny of ritualization in man. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 251(772), 337-349.

- 1966. Youth: Fidelity and diversity. In Conflict Resolution and World Education (pp. 39-57). Springer, Dordrecht.

- 1964. Inner and outer space: Reflections on womanhood. Daedalus, 582-606.

- 1962. Reality and Actuality an Address. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 10(3), 451-474.

- 1958. Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History. W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1958. The nature of clinical evidence. Daedalus, 87(4), 65-87.

- 1956. The problem of ego identity. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 4(1), 56-121.

- 1954. The dream specimen of psychoanalysis. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 2(1), 5-56.

- 1950. Growth and crises of the” healthy personality.

- 1946. Ego development and historical change: Clinical notes. The psychoanalytic study of the child, 2(1), 359-396.

- 1942. Hitler’s imagery and German youth. Psychiatry, 5(4), 475-493.

Citatie voor dit artikel:

Janse, B. (2021). Erik Erikson. Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.nl/bekende-auteurs/erik-erikson/

Gepubliceerd op: 14/07/2022 | Laatste update: 20/03/2023

Wilt u linken naar dit artikel, dat kan!

<a href=”https://www.toolshero.nl/bekende-auteurs/erik-erikson/”>Toolshero: Erik Erikson</a>